Sibelius’s Kullervo is an undoubted masterpiece… but boy, is it a quirky one. By all conventional rules of classical musicdom, it simply should not be. Consider:

- It was the first significant orchestral work Sibelius ever wrote.

- It came from Finland, which at the time was distant corner of the Russian Empire that did not have a particularly strong or well-developed classical musical infrastructure.

- It featured singers singing in Finnish—a language that was looked down upon as being low-brow at the time.

- It chronicled the adventures of a decidedly unconventional hero from Finnish mythology.

- It was only performed five times before Sibelius withdrew it and banned all future performances of the work; it was only after his death that his heirs authorized the work to be performed again.

In short, Kullervo is an oddity, an enigma… much like the legendary figure upon which it is based.

But make no mistake, it is a masterpiece that is as startling today as it was at its premiere in 1892. It is the work that created Sibelius’s reputation. And it is a work I love to distraction.

.

The reason it survives is the quality of the music. In early years it was customary to tut-tut elements that were seen as “youthful indiscretions” in composition. Admittedly, Sibelius does make a few clumsy choices in scoring here and there and doesn’t always follow conventional rules of harmonic writing. His style of vocal writing is hardly groundbreaking.

But to carp about these things is to miss the point of the work entirely. Most of these problems are technical issues that trouble musicologists and theoreticians rather than listeners, who get swept up in the work’s originality, power, and staggering drama.

It is, quite simply, epic.

The premiere, led by Sibelius himself on the podium, was a success the likes of which few composers have enjoyed in their lifetimes. Sibelius had been so nervous about the performance that he nearly worked himself into a panic attack beforehand. But he need not have worried—at the conclusion of the work, he turned to find the audience on its feet with a thunderous ovation… and himself to be Finland’s new national hero.

* * *

The story of Kullervo is dark, which should feel familiar to any fan of Wagner’s Der Ring des Nibelungen… or for that matter, the popular show, Game of Thrones.

In the ancient past, there was a blood feud between two clans, who were led by two estranged brothers named Kalervo and Untamo. Untamo led a surprise attack on his rival’s stronghold, leading to a general massacre of everyone they could find. Later amid the devastation, Untamo came upon Kalervo’s infant son, Kullervo. Whether he was motivated by a sense of atonement, or a desire to keep a potential enemy close, Untamo took the child and vowed to raise him.

Kullervo’s upbringing was rough, surrounded by enemies who hated him and denied any comforts or moral education. In time he became a wild child—noted for his temper, but also clearly instilled with powerful, if latent magic powers. Untamo began to fear his young ward and secretly tried to kill him, but Kullervo’s powers kept him alive. Finally, Untamo decided to rid himself of the boy by selling him into slavery.

Out of the frying pan, and into the fire.

His new master Ilmarinen treated him roughly but fairly, but was unable to tame Kullervo’s temper. Ilmarinen’s wife took particular delight in tormenting him, at one point causing him to break his knife… the one keepsake he had from his birth parents. In a violent rage Kullervo called forth powerful magic that led to the woman’s death, and he fled into the forest for shelter.

But here things take a strange turn. In the forest, he came across his true mother and father, who had managed to escape the Untamo’s massacre, living in hiding and planning their revenge. Kalervo later sent Kullervo across the clan lands to pay taxes… but unfortunately, at this point Kullervo’s ill-fortune dealt him the cruelest blow of all.

Along his journeying, Kullervo met a young woman. He was immediately enraptured by her beauty and pulled her into his sled. She initially resisted his advances, but his soft words slowly enticed her, and the sight of the clan’s treasure convinced her that he was wealthy beyond measure. Stories being stories, she surrendered to his charms.

Some time later, they asked about each other’s lineage and backgrounds. She told a tale of woe—many years ago she wandered away from home as a little girl and became lost. She lived alone in the woods as a wildling ever since, surviving on her own. But she noted that she came from a great lineage, descended from a great man named Kalervo. At this point, a horrified realization crept over the lovers—they were long-lost siblings. In shame, the sister fled to a near-by river and drowned herself.

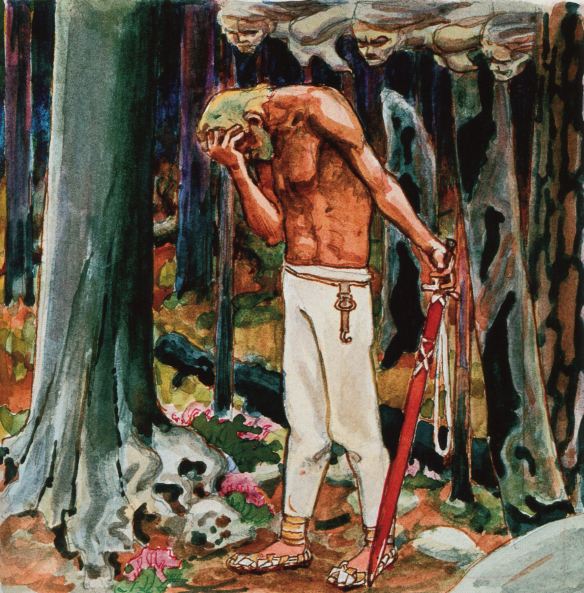

The grief-stricken Kullervo vowed to destroy his uncle Untamo, the source of all his family’s misfortune. He obtained a mighty sword forged by the storm god Ukko, and marched off to war. As the battle raged, he fought savagely and recklessly, seeking not only to slay his enemies but to find redemption through an honorable death on the battlefield. But even here he failed. Instead of dying, he won the day, and in the midst of his triumph realized he had become a monster.

Tormented, Kullervo wandered alone until he came upon the site where he seduced his sister; to his horror, he saw that the spot was blighted and cursed, as if nature itself shunned him. That final realization was too much to bear, and with grief and self-loathing, he committed suicide by falling on his enchanted sword.

.

The tale is a grim one, but it had great resonance in Finland during the 19th and 20th centuries, while the country was still under the heel of Imperial Russia. Finns saw Kullervo as a metaphor for their own fate—born under an unlucky star, and constantly thrown into hard situations by outside powers. Unable to catch a break. It seems that everything they did turned against them and they could never make use of their own latent powers. The visionary Aleksis Kivi wrote a play on the theme, and several Finnish composers wrote music inspired by the tale, with Aulis Sallinen’s opera Kullervo appearing in 1988.

It was not just Finns who were drawn to the story. J.R.R. Tolkien was a particular fan; he reworked the plot into the tale of “The Children of Húrin” which was alluded to in The Silmarillion and published as a stand-alone novel (posthumously) in 2007. Tolkien also attempted a direct novelization of the legend, left unfinished at his death, which will be published later this year.

* * *

Sibelius’s interpretation of the Kullervo story remains the most powerful and arresting of them all. From the beginning, Sibelius chose to hew as closely as possible to the original text as it appeared in the Kalevala—Finland’s epic poem that was originally meant to be sung. As a result, the story isn’t dramatized, but simply presented like an oratorio, with a male chorus narrating and commenting on the action.

The music does not make direct use of ancient music, but strives to create the feel of a timeless ritual.

The first movement Introduction serves to set the stage; it is a purely orchestral movement that conveys the mood of the work and the ancient world in which it is set. It also introduces musical themes that reappear later and bind the work together. It is somber, but filled with a stark grandeur.

Following the introduction is the second movement, “Kullervo’s Youth,” which is also instrumental and tells the story of Kullervo’s troubled upbringing. One of the details that stands out for me is a gentle, rocking motif of a long held note followed by a quick succession of short notes. It is introduced at the very beginning, where it has the feel of an ancient lullaby, supportive and serene. As the music becomes more agitated, the character of this motif changes, becoming desperate and gasping. At the end, this same motif is completely changed into a snarling cry of defiance, mirroring Kullervo’s transformation from a promising boy to an agent of vengeance.

The third movement, “Kullervo and his Sister,” is the emotional and musical core of the work. It is scored for soloists representing Kullervo and his sister, supported by the male chorus and full orchestra. And it is magnificent. The chorus tells of Kullervo departing to pay the clan’s taxes, and his unsuccessful attempts to find romance along the way. Finally he sweeps his sister into his sleigh. At first she angrily fights him off, yet the chorus tells how Kullervo’s soft words and accumulated treasure break her resolve. Their subsequent love-making is depicted by orchestral music that is passionate, yet tinged with a sense of foreboding. After their ill-fated tryst, the lovers tell each other of their family backgrounds. At this point the sister sings an astonishing aria that tells how she became lost in the woods so long ago, with music charged with profound loneliness and terror. It is also filled with a growing sense of despair as she realizes she has unknowingly committed incest. At the end, she chooses to drown herself rather than live with her shame. After a pause of devastating silence, Kullervo sings a lament, which contains some of the most riveting vocal music Sibelius was ever to write. He rails against the many hammer-strokes of fate and vows to destroy his family’s enemies with music that is equal parts searing and terrifying.

Sibelius follows this with the purely instrumental fourth movement, “Kullervo Goes to War”—a wide-ranging, energetic eruption of sound to balance the tightly focused family drama of the third movement. It is cinematic in is depiction of battle, bristling with brass and heroic flourishes.

The finale, “The Death of Kullervo,” features the male chorus and orchestra as it brings the story to its conclusion. Here Sibelius goes for broke; the music is hugely dramatic and inventive, matching the conflicted and increasingly desperate hero. It builds to a stunning finale that thunders to the heavens.

[Click here for my follow-up post on Kullervo’s ever-present and faithful dog—a small but distinctive part of the legend.]

Kullvero is a formidable work, but to really shine it needs dedicated performers to bring the ancient tale to life. And we have just such a collection of performers coming to Orchestra Hall this week. Back in 2010, I had the good fortune of hearing Osmo lead the Minnesota Orchestra and Finland’s YL Male Chorus (Ylioppilaskunnan Laulajat). The direction was outstanding, as were the orchestra and the soloists. In fact, when these same forces performed at Carnigie Hall weeks later, the great Alex Ross of The New Yorker said the Orchestra sounded like the “greatest orchestra in the world.” As an aside, I suspect that quote has been used in every marketing piece the Minnesota Orchestra has subsequently produced.

All this is true, but what I remember most from the concert was the YL Chorus’s singing. This was male singing at its finest, with rich tone, vocal power, and flawless delivery… clearly, this work is in their souls. Their singing not only effortlessly captured the shifting narrative of the piece, but spoke to the underlying emotions, too. And at the key moments, their combined sound was like a force of nature. It was a performance for the ages. Plus, they followed it up with a choral rendition of Finlandia that was beyond magnificent… even the non-Finns in the audience were ready to take up arms by the end!

So… simply put, this concert is mandatory. Visit the Minnesota Orchestra box office right this very minute to get your tickets.

.

Pingback: Kullervo’s Dog | Mask of the Flower Prince

I’m glad to get this post just in time for the concert tomorrow morning. What a story and a tragic Finnish (couldn’t resist). Beautiful pictures too.

LikeLike

Pingback: El Kalevala (PARTE II) | Leyendas Europeas

I discovered Kullervo recently while browsing around on YouTube. It is absolutely entrancing and deserves to be better known.

LikeLike

Thank you for posting a really informative and interesting item about one of my favourite works, if not THE favourite work. It is no exaggeration to say that when I heard this as a teenager in 1978 I was instantly smitten with it, and of all the music I have heard, studied and learned, this one composition was the greatest motivation to me to compose music. Fast forward to 2000 and finally after completing 12 symphonies I finally felt able to write my own “Kullervo” Symphony. It is a homage to the Great Sibelius, the not as brilliant as his work. It can be found on youtube, if you would like to hear it. Best wishes, and thanks again.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Grahame: Went to have a listen on YouTube. It’s really nice, and does remind somewhat of Siberlius’ version. I’m definitely going to explore some of your other work there as well.

LikeLike

Hello Brian. Really pleased you find some pleasant aspects of my version – my main influences have always been Scandinavian and Russian. In a couple of works I sound ‘Sibelian’ though more often reminiscent of Shostakovich. But hopefully I have also acquired my own sound. All the best. Grahame.

LikeLiked by 1 person